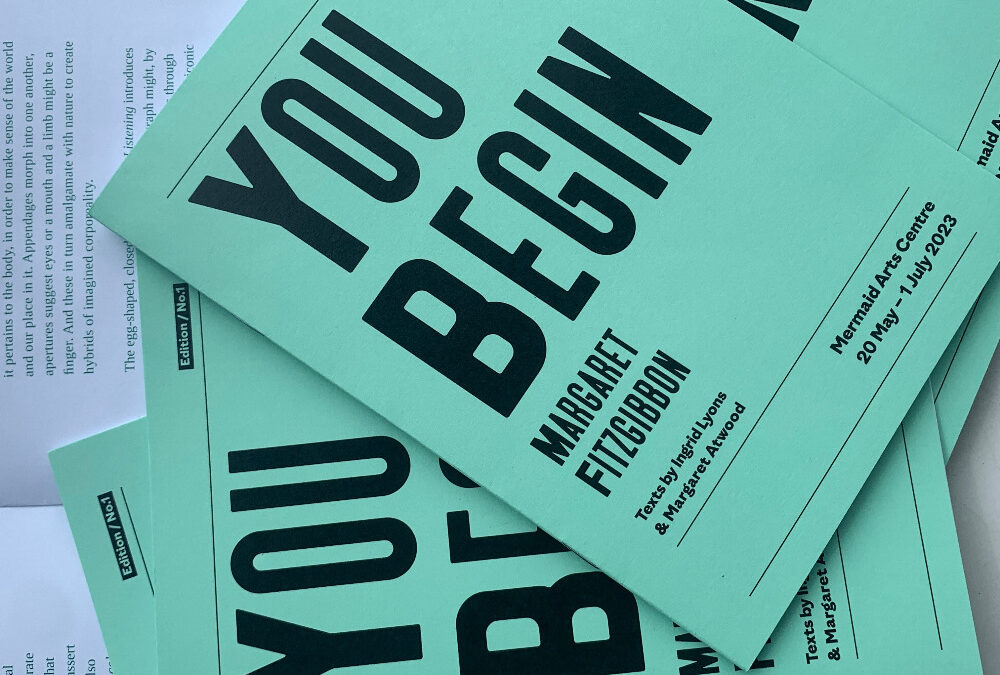

The show is accompanied by a micro book with a commissioned essay by Ingrid Lyons

Margaret Fitzgibbon

You Begin

The title of the exhibition, borrowed from the Margaret Atwood poem sets the tone for a meditation on what feminine creativity looks like and how this might be conveyed. By centering the exhibition on Margaret Atwood’s poem, ‘You Begin’ Fitzgibbon opens up a dialogue with the audience, eking paths into the work through this casual yet universal piece of writing. The poem returns again and again to the profundity of what it means to use our hands to create. It is so basic and seemingly simplistic a concept that we nearly forget to think about it. Atwood’s poem which takes on a gently instructive tone intimates that the speaker is teaching the listener something. It points and guides our inward eye. It centres our gaze and asks us not only to see, but to think about how we see.

You begin this way:

this is your hand,

this is your eye,

that is a fish, blue and flat

on the paper, almost

the shape of an eye.

Atwood’s poem seems to suggest, we make sense of the world by shaping it and casting it according to our observations.

The artworks in ‘You Begin’ tread the line between realism and fantasy incorporating references to Surrealism. Many of Fitzgibbon’s works speak to this alternative canon and the contribution of women in terms of the hierarchy of materials. There are numerous references to the sea which connect these objects and images topographically and to the act of making. Hands act as a guide, a vessel or maybe a catalyst for transformation.

The act of creating a likeness of a hand with a human hand comments on our perception of the body according to the viewpoint of the artist. It signifies a restoration of the gaze from the art historical male perspective to the experiential female perspective. Such references to figuration proliferate throughout the exhibition. Representations of the body that beget representations of the body in a generative effect assert ingrained or instinctual impulses towards creativity. It also calls to mind the sand casts made by lugworms or Arenicola marina on beaches at low tide. These mounds which can be seen on muddy-sandy shores around the coast of Ireland, are made when the worms burrow under the wet sand. They eat the sediment, assimilating nutrients before redepositing their spiral mounds. They leave their distinctive marks of subterranean life by casting themselves on the surface.

Patterns from the coast often make their way subtly into the work as suggestions and inferences. The shell of a spider crab pressed into clay, cephalopod limbs emerging from orifices or tentacles reaching outward or coiling upwards. Some appear almost botanical, like seaweed, others are anthropomorphic looking and conjure creatures from the depths of the sea.

A number of the works are created from Porcelain, a medium that is challenging to manipulate by hand with its chalky fragility. Fired, it stabilises and though it is still delicate, it’s texture and porosity emulates skin. This creates a mutuality of surfaces as we enter and inhabit the world of embodied objects. The assemblages and forms that make up ‘You Begin’ have a votive and ritualistic quality where they look upon the roll of object making as it pertains to the body, in order to make sense of the world and our place in it. Appendages morph into one another, apertures suggest eyes or a mouth and a limb might be a finger. And these in turn amalgamate with nature to create hybrids of imagined corporeality

The egg-shaped, closed form of Close Listening introduces us to various themes in the works as an epigraph might, by paying homage to Fitzgibbon’s artistic influences through quotes in motif and materiality. In her referencing of iconic works by surrealist artists, she emphasises a number of touchstones which she revisits throughout the exhibition. We might think of the repertoire of Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli and her earrings made of cast ears, her golden gloves made of cast fingers. Close Listening might also refer to the way a child lifts a shell to their ear to hear the sea. A fiction that we share with one another as though an object from the sea can also conjure the sea. Such tongue-in-cheek correlations are recurrent throughout this body of work.

In the Palm of her Hand, depicts a hand, extended outwards, facing upwards. A tentacle pierces through the open palm as though in a reverse stigmata. Shell and Hand speaks to French surrealist artist Dora Maar’s Untitled (Shell hand), 1934. Each sculpture simultaneously approaches the western canon of art history and the artists own embodied relationship with the materials to glean an understanding of the legacy of ideas. There are allusions to eroticism and animality through use of visual analogy in flora and fauna, subversive innuendo as it has appeared in the lexicon of surrealist symbolism. Furry Fingers, continues a dialogue in its referencing of Swiss surrealist artist Méret Oppenheim’s, Object (Le Déjeuner en fourrure) 1936, a fur-covered teacup, saucer and spoon with a salacious back story. As with other surrealist works, a visual gag is implied. Fitzgibbon’s playful refrain chimes back at this iconic piece with recognition of its significance within the surrealist oeuvre. Humour and double entendre recur throughout. Snakey Snakey functions allegorically within the exhibition representing a clash between symbolism and materiality associated with gender performativity. Here, the male tie is singled out as an ‘appendage’ for special scrutiny as an object of declarative masculinity that acts as both a mask of traditional respectability and hidden power.

The spirit of Surrealism which originated in the late 1910s and early ’20s was with experimentation in new modes of expression to release the unbridled imagination of the subconscious. It sought to represent cataclysmic cycles of change and turbulence during the beginning of the 20th Century. The works in ‘You Begin’ span a time of great upheaval 2020 – 2023 and consequently are indicative of the disembodied world that we inhabited together. We might remember how vivid dreams were commonly described as part of the lockdown experience. The casual presence of others dwindled from our daily lives and many people tried to spend more time in nature seeking out tactility, texture and sensory experience within the limits of their dwelling place.

Margaret Fitzgibbon’s enigmatic sculptural works and visionary drawings and collages, created during this time of significant change, form a treatise on the history of Surrealism. The artworks in ‘You Begin’ reinvigorate a discussion on figuration in art and this series of works suggests fresh relevance in light of contemporary feminist discourse and recent collective experience.

Recent Comments